Robert Bloom as a young man in Pittsburgh.

Background Information

Birth name: Royal Israel Bloom (Robert Irving Bloom)

Born: May 3, 1908; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Died: February 13, 1994; Cincinnati, Ohio

Parents: Ida Fisher Bloom and Reverend Julius Bloom

Marriages: Victoria Murdock, divorced

Miriam Wallner, divorced

Sara Lambert

Children: Katharine, Jonathan, and David with M. Wallner, Julia with S. Lambert

Education: Carnegie Institute of Technology, cello major 1925-1927

Curtis Institute of Music, oboe major 1927-1930

Diploma, Curtis Institute of Music 1935

Genres: Orchestral, chamber music, solo; 18th, 19th, and 20th century repertoire

Occupation: Oboist (and English hornist), recording artist, teacher, composer, conductor, editor of 18th-century masterworks

Years active: 1930–1993

Philadelphia Orchestra, Rochester Philharmonic, NBC Symphony Orchestra, various recording orchestras, Bach Aria Group, Yale University School of Music, Juilliard School, Eastman School of Music, various other teaching institutions and festivals, including the Sarasota Music Festival

Robert Bloom (May 3, 1908 – February 13, 1994) was one of the foremost American oboists. Often hailed as one of the last performers of the Golden Era of classical music, a “grand, grand artiste” in the words of Pablo Casals, called “caro” by Arturo Toscanini, and a favorite of other conductors ranging from Leopold Stokowski to Igor Stravinsky to Robert Shaw, Bloom was an orchestral oboist and English hornist, oboe soloist, chamber musician, teacher, composer, conductor, editor of 18th-century masterworks, and, as a founding member of the Bach Aria Group, a seminal influence in the post-WWII revival of Baroque music in America, building on performances that he gave and recordings that he made during the two decades prior to the founding of the Bach Aria Group by William H. Scheide in 1946.

Contents

- Youth and education

- Orchestral career

- Solo and chamber music career

- Composing, transcribing, elaborating 18th-century masterworks

- Posthumous archival work

- Teaching and mentoring

- Honors

- Personal Influence

- Summer breaks and hobbies

- Pupils

- References

- External links

- Profile of Robert Bloom by Daniel Webster

- New Haven Register quote by Gordon Emerson

- Robert Bloom: A Biographical Sketch by Jerome Hoberman with Robert Bloom

Youth and Education

Bloom was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father, Julius Bloom, was Pittsburgh’s leading cantor who, besides officiating in the city’s synagogues, was an outstanding choir director and composer. Reverend Bloom had fled the pogroms that occurred in his native Kiev in the late 19th century, as did his future wife, Ida Fisher. The family was musical; Jennie, one of Bloom’s five sisters, was an excellent soprano and pianist and his brother, William, was a violinist who became a member of Walter Damrosch’s New York City Symphony and later the New York Philharmonic after the merger of these orchestras. As a boy, Bloom sang in his father’s choir and studied several instruments while attending local public schools. He entered Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology as a student of cello and music education in 1925. He was encouraged to take up the oboe seriously by early teachers Joseph Derdyne and Oscar W. Demler, his music teacher at Fifth Avenue High School (who later became the Music Supervisor of the Pittsburgh Public Schools and the conductor of Pittsburgh’s All-City Youth Orchestra). With the recommendation of Professor W.O. Schultz , one of his teachers at Carnegie Tech (now called Carnegie Mellon University), Bloom auditioned in 1927 and won a place in the oboe class at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, which had been founded just three years earlier.[1]

At Curtis, his major teacher was Marcel Tabuteau, long-time Principal Oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who is generally thought of as creator of the American school of oboe playing. Later in life Bloom readily confirmed that Tabuteau was less interested in the past experience of potential students than in their aptitude for the oboe, and was quite willing to take on someone who was virtually a novice. On the occasion of Bloom’s 80th birthday, which was celebrated with a marathon concert at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center in May 1988, Dean Robert Fitzpatrick read from the statement of purpose that Bloom submitted during his application process: “to become an oboe player, conductor, and composer,” and from Tabuteau’s evaluation after hearing young Bloom play: “very promising.” Bloom earned the mantel of “pioneer” early on. Oboist Laila Storch provides this interesting history when writing about the alma mater she shared with Bloom: “From the time of its opening in the fall of 1924, one of the major aims of the Curtis Institute of Music was to train first-class orchestral musicians in all instruments… Beginning in 1926, the ‘Students’ Orchestra’ at Curtis presented concerts under the direction of Leopold Stokowski or Artur Rodzinski. At first the concerts featured only single movements of symphonies or concertos, but they soon developed into full-fledged programs. The names of the students in the violin section read like a page from a future Philadelphia Orchestra program. But the lack of advanced wind students is evidenced by Marcel Tabuteau’s name as first oboe along with Louis Di Fulvio, the second oboist from the Philadelphia Orchestra. Although orchestral, piano, and string playing were beginning to flourish at Curtis, it was not until 1930 that ‘Students of Mr. Tabuteau in Wind Ensemble’ could be featured during a season that included recitals by students of other eminent faculty members…The date was February 10, 1930, and it would mark the beginning of that unique yearly event, the Tabuteau Ensemble Class Recital …The oboist for every work was Robert Bloom.”[2] In February 1931, during his first year as a member of the Philadelphia Orchestra, Bloom took part in a concert at the Curtis Institute featuring “Artist-Students” under the direction of Dr. Louis Bailly, the renowned violist, who was head of the Department of Chamber Music. It apparently would take a few more years after Bloom’s matriculation for Tabuteau to build his stellar class, with Bloom invited back on occasion to bridge the gap.

Orchestral Career

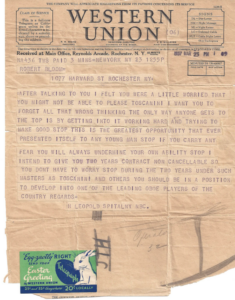

Appointed by the conductor without having auditioned, Bloom joined the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski in 1930, first as Assistant Principal Oboist and the following year as Solo English hornist after just three years of study at Curtis. In May 1935, he was awarded his diploma from the Curtis Institute of Music. Leaving the Philadelphia Orchestra after six seasons, Bloom became Principal Oboist of the Rochester Philharmonic in 1936 at the invitation of its conductor, Jose Iturbi, who had just lost out to Ormandy in his bid to succeed Stokowski in Philadelphia. In 1937, with the formation of the NBC Symphony Orchestra in New York, Bloom was offered the position of Principal Oboe by Artur Rodzinski, who was organizing the orchestra for Maestro Arturo Toscanini and who, as conductor of the Curtis Orchestra while Bloom was a student, knew his playing well. Despite misgivings due to his limited experience as a first-chair player, Bloom accepted the post, encouraged in this decision by Jose Iturbi and by the telegram from NBC’s personnel manager, H. Leopold Spitalny, offering a longer contract when he did not accept the first offer. Bloom remained with Toscanini and the NBC Symphony until 1943, when he resigned over the issue of having to play what he called “cafe music” that the orchestra was programmed to broadcast during the weeks that Toscanini was not conducting. Bloom’s heartfelt letter to the Old Maestro reads in part: “I would put up with almost any condition to have the privilege of playing under you, Maestro, but I do not feel it is right for N.B.C. to take advantage of that fact. By my actions in the past, you know of my love and respect for you, and I feel very sad that I will not be working under you. Thank you from my heart for all you have taught me and all you have done for me.”[3]

Just two auditions, then, launched a career that lasted more than six decades: Bloom’s audition for the Curtis Institute of Music in 1927 and his successful audition in 1930 to become the assistant to principal oboist Philip Kirschner in the Cleveland Orchestra under Nicholai Sokolof. It was this offer that prompted Leopold Stokowski to hire Bloom for the Philadelphia Orchestra without a formal audition by directing his personnel manager, “You tell that young man that it is closer to the Academy of Music from Curtis than it is to Cleveland.”[4]

Following Bloom’s resignation from the NBC Symphony in 1943, during the next period of his career he was active in recording studios in New York as Principal Oboist for Columbia, Decca, and RCA Victor Records under conductors such as Fritz Reiner, Otto Klemperer, Leopold Stokowski, Artur Rodzinski, William Steinberg, Igor Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Wallenstein, Sir Thomas Beecham, Josef Krips, Karill Kondrashin, Renato Cellini, Eric Leinsdorf, Dimitris Mitropoulos, Robert Shaw, Jean Morel, Jose Iturbi, Morton Gould, Izler Solomon, Robert Russell Bennett, Leroy Anderson, and Bruno Walter, among others. Many of these classic recordings remain available in current catalogues, reissued in CD format. While most repertoire were new works composed by contemporary masters including Bernstein, Stravinsky, and Milhaud as well as masterworks composed during the previous three hundred years, Bloom also enjoyed being called by Jackie Gleason to record an album with the jazz greats of the day, by RCA Victor to record Hebrew Melodies with Jan Peerce, to record film scores, and even love songs such as “The Night Was Made for Love,” a Kern and Harbach song composed for The Cat and the Fiddle, an early MGM Musical that was recorded by Nelson Eddy and Jeannette MacDonald, popular idols of the day. Bloom’s objection to the programming of “lighter” repertoire by the NBC Symphony reflected his reverence for Maestro Toscanini’s symphony orchestra here in America (a reverence no doubt developed as a young member of the great Philadelphia Orchestra) but did not preclude his taking part in such recordings and broadcasts in commercial settings including the Bell Telephone Hour and the Conte Shampoo program. An updated discography that shows this range is being maintained on the https://robertandsaralambertbloom.com” website.

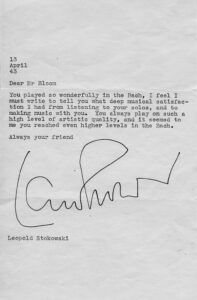

During this final period of orchestral activities in New York, Stokowski remained a close collaborator, writing personal letters to Bloom frequently with invitations to perform with him and asking Bloom to recommend other players. Stokowski also sent messages complimenting him on his playing as he did in a letter dated April 13, 1943: “Dear Mr. Bloom, You played so wonderfully in the Bach, I feel I must write to tell you what deep musical satisfaction I had from listening to your solos, and to making music with you. You always play on such a high level of artistic quality, and it seemed to me you reached even higher levels in the Bach. Always your friend.”[5]

Solo and Chamber Music Career

Bloom also distinguished himself as a soloist and chamber musician, with appearances throughout the United States and in South America, Europe, and Israel. Mainstays of his solo repertoire were his own Requiem for Oboe and Strings, his own edition of the Concerto in Eb Major, Helm 468, Wq XXI, No. 165 composed by C.P.E . Bach, the Double Concerto, BWV 1060, composed by J.S. Bach, and a dozen or so concertos composed by other 18th-century composers including Handel, Marcello, Cimarosa, Telemann, and Vivaldi. Although too late for him to perform them, Bloom was particularly pleased when more concertos of a lyrical, “romantic” nature were written for the oboe by composers including Harbison, Barber, Corigliano, and others, adding to those he loved written by Sibelius (Swan of Tuonela for English horn and orchestra), Vaughn Williams and (unfortunately) just a few other composers. Bloom’s chamber music repertoire was selected from baroque, classical, romantic, and contemporary works and he particularly favored works for mixed ensemble rather than for just winds.

William H. Scheide

Two years after leaving NBC, Bloom was invited to become a founding member of the Bach Aria Group, which became a seminal influence in the postwar revival of Baroque music in America. The Group, composed of 9 members (flute, oboe, violin, cello, keyboard, soprano, alto, tenor, bass) plus its founder and Artistic Director, William H. Scheide, presented 3 concerts with orchestra and chorus annually in NYC, first at Town Hall and then at Tully Hall. Beginning in 1946, the Group gave the American premiere performance of many of Bach’s cantatas and selected arias, and also made many first recordings on M-G-M, Vox, Decca, and Desto labels. Weekly radio broadcasts brought the message of Bach’s cantatas to Americans of all economic strata, Scheide’s egalitarian mission, reaching millions who could not attend concerts or purchase record players or recordings. These compositions were Bach’s self-declared “Endzweck,” which translates to “ultimate purpose,” not simply a “life goal,” and were compared by many to the treasures of literature found in Shakespeare. Touring America annually, the Group also appeared abroad at the Casals Festival in both Prades and Puerto Rico, the Israel Festival, and on numerous artist series in Europe and South America. Bloom retired from the Bach Aria Group in 1980, at which time Scheide also announced his retirement and ended the 34-year association that was made possible by Scheide’s brilliant scholarly study of the repertoire and his genius at being able to direct (but never conduct or perform with) the ensemble that he hand-selected.

Scheide told the gathering at Bloom’s 80th Birthday, “We had thirty-four years’ association in that work of getting together a man like Bob Bloom with a man like Johann Sebastian Bach, and it’s been one of the richest experiences of my life and a very unique one. We shared many, many things and sometimes I thought of him as an older brother to me. We had a relationship, an intimacy transcending mere music. We talked about the Group in general and shared interests in many different ways…I remember hearing his playing of the ritornel of the great aria from Cantata 82 for bass in which there is an oboe solo that Bob first encountered in our first summer and I thought to myself (and I still do think), ‘That is the greatest performance I ever heard anywhere…by anybody…of anything,’ and I might be wrong, but I think he looked around as if to ask, ‘Did any of you appreciate what I was doing?’ and I thought to myself, ‘I do.'”

Notwithstanding Bloom’s distinguished career as an orchestral principal oboist at the highest level in America and as a pioneer oboe soloist, he called his work with Scheide and the Bach Aria Group the “highlight” of his career and always added that he could never really believe that he was getting paid to play Bach, a favorite quip that Scheide, who funded the Group, never tired of hearing. Bloom said of Scheide, “Here is a man who thought that if we heard more of the sacred works of Bach, the whole world would be better.”[6] Calling it his “private Bach,” Scheide recognized early on that the cantata repertoire was not likely to be widely heard if he did not create the ensemble and provide the direction and funding since it was not something that would survive in the market-driven world of presenters. Bloom and Scheide held each other in rare esteem.

A reviewer for the Deseret News wrote of a concert of the Bach Aria Group presented in Salt Lake City in 1960, “To hear the almost unbelievably imaginative penetration of such virtuosos as Mr. Bloom, who gave us things we had never before heard from an oboe, Mr. Baker, Mr. Shumsky, and Mr. Greenhouse, is one of the great aesthetic privileges of our time.”[7]

To understand Bloom’s own “Endzweck,” one can examine his response to three questions: what, how, and why to play music. His resignation from the NBC Symphony illuminates his determination to play only music that shapes our humanity; his intense study of composition, 18th-century performance practices, and the polemics of musicianship illuminates his attention to learning and then teaching how music should be played; and finally, his end-of-life gestures to honor his father and express gratitude for his association with Scheide, the “bookend” towering figures in his life, illuminate Bloom’s constancy. He never wavered, regardless of financial considerations, in his devotion to his personal conviction of not just what to play and how to play; he was also able to live his life guided by a profound sense of why to play.

Composing; Transcribing; Elaborating 18th-Century Masterworks

Affiliation with Otto Luening at Columbia University and Bennington (as his composition student and musical colleague), led Bloom to compose seven compositions, mostly in the 1950s: Aria for oboe and piano; Sonatina for oboe and piano; Sonata for violin and piano; Requiem for oboe and strings (composed in memory of his father); Narrative for oboe and strings; Madrigal for oboe and piano (dedicated to his wife Sara and later transcribed for oboe and strings). He also composed a very early work titled Lullaby from the Steppes. Bloom composed concerted cadenzas for Beethoven’s Trio Opus 87; Mozart’s Divertimento in D Major, K. 251; and Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major, K. 297b/Anh. C12.01. He was pleased to have carried on the tradition of instrumentalists composing for their instrument, as did his early New York oboist-colleague Bruno Labate, and later, Ronald Roseman, Bo Nathan Newsome, and Jeffrey Rathbun among others. Bloom loved to transcribe works for the oboe, a fruitful activity that was also taken up in a serious way by the Louis Rosenblatt.

Many of Bloom’s New York, Bennington, and Yale colleagues composed works for him, among them Otto Luening (Legend for oboe and strings (1950),Three Nocturnes for oboe and piano (1951), and Divertimento for oboe and string trio (1988)); Tibor Serly (Oboe Solo); Lionel Nowak (Sonata (1949) and Quartet for oboe and strings); Richard Donavan (Music for Six (1961) and Serenade for oboe and string quartet (1965)); Roger Goeb (Wind Quintet); Jean Berger (Sonata da Camera (1949) later transcribed for oboe and string quartet); Hunter Johnson (Trio for Flute, Oboe, and Piano); Quincy Porter (Quintet for oboe and string quartet (1966)); and Fredrick Kaufman (A Bud for Bloom for flute, oboe, and piano (1988)). Bloom played the premiere of other chamber works, including Bohuslav Martinu’s Rhapsody for theremin, oboe, string quartet, and piano commissioned in 1946 by Lucy Rosen, and the famous transcription of J.S. Bach’s “Es ist vollbracht” that Bloom (English horn) and Walter Goetter (bassoon) recorded with the Philadelphia Orchestra strings with Stokowski conducting. Another favorite work was Wayne Barlow’s The Winter’s Passed (1938) that Bloom performed with the NBC Symphony strings for a radio broadcast conducted by Toscanini in 1940. Although the score is not dedicated to Bloom, Barlow, who was completing his PhD as a pupil of Howard Hanson during Bloom’s one year on the faculty at Eastman, 1936-1937, might have composed it for him. Remaining connected to his Eastman colleagues, Bloom often programmed Hanson’s Pastorale for oboe and strings (1949), which was commissioned by UNESCO for the Chopin Centennial in Paris.[8]

Posthumous Archival Work

After his performing career ended, Bloom remained active as a composer, with works he composed for oboe with strings and oboe with piano performed frequently throughout the world. In addition, Bloom’s elaborations and cadenzas for much of the standard oboe repertoire of the Baroque and classical periods were regularly in use, with and without authorization. In 1998 Bloom’s widow, Sara Lambert Bloom, finally realized her late husband’s request and published The Robert Bloom Collection, scores and parts to his 21 editions of 18th-century masterworks, 10 transcriptions, and 10 compositions; several more releases are planned as well as piano reductions for the concertos. The Collection, including Mrs. Bloom’s prefaces, earned accolades around the world, including the comment, “The service that Mrs. Bloom has rendered to our art, and by extension, to our culture (world wide) is beyond measure.”[9] Mrs. Bloom, an oboist and former pupil of her husband’s at the Yale School of Music where she earned her M. Mus. degree in performance, published in 2009 Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, a compendium of Bloom’s oboe pedagogy, preferred curriculum, published and unpublished essays, discography, selected correspondence and reviews, transcriptions of interviews in which some of America’s most prominent musicians discuss with him the art, the politics of the art, as well as anecdotes from milestone events, career highlights of the man” generally considered to be one of the greatest oboists of his generation and perhaps of all time.”[10]

In addition to his formal education followed by collaboration with eminent musicians and scholars of his day, Bloom drew from the insights he learned by reading primary sources, most importantly the collected letters of the Mozart family, as well as the scholarly books on the interpretation of 18th-century music authored by Robert Donington and others.

Bloom was one of the most recorded oboists of the 20th century, but could not be persuaded to record repertoire for solo oboe and chamber works for major labels. Adding to his commercial recordings that remained mostly of orchestral works, then, The Art of Robert Bloom, a 7-CD set of live performances of concertos, chamber music, and Bach arias performed by Bloom over his extraordinary 60-year career was released in 2001 on Boston Records label, a project again directed by Mrs Bloom, who wrote extensive liner notes. Calling Bloom’s playing “cynosure,” brilliant enough to navigate by, Bernard Jacobson, program annotator and musicologist of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Artistic Director of the Residentie Orkest, The Hague, considers Bloom “a player of phenomenal gifts, not merely technical, though in that sphere he can have had few rivals, but in the field of musicianship, of expressivity, and also–a salutary revelation in these days when we think we are the first generation to have discovered the truth about Baroque style–of taste in the interpretation and embellishment of eighteenth-century texts.”[11]

Bloom was one of the most recorded oboists of the 20th century, but could not be persuaded to record repertoire for solo oboe and chamber works for major labels. Adding to his commercial recordings that remained mostly of orchestral works, then, The Art of Robert Bloom, a 7-CD set of live performances of concertos, chamber music, and Bach arias performed by Bloom over his extraordinary 60-year career was released in 2001 on Boston Records label, a project again directed by Mrs Bloom, who wrote extensive liner notes. Calling Bloom’s playing “cynosure,” brilliant enough to navigate by, Bernard Jacobson, program annotator and musicologist of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Artistic Director of the Residentie Orkest, The Hague, considers Bloom “a player of phenomenal gifts, not merely technical, though in that sphere he can have had few rivals, but in the field of musicianship, of expressivity, and also–a salutary revelation in these days when we think we are the first generation to have discovered the truth about Baroque style–of taste in the interpretation and embellishment of eighteenth-century texts.”[11]Costs to produce these resources were partially covered by large and smaller gifts from dozens of colleagues and friends. Information about the Collection, book, and CD archive can be found on the https://robertandsaralambertbloom.com website.

Teaching and Mentoring

Beginning with his one year in Rochester, Bloom was continuously active as a private teacher with a studio in his various homes and at Carnegie Hall, and as Professor at Eastman (1936-37), Yale School of Music (1957-76), Hartt (1967-75), the Manhattan School of Music (1967-72), the Juilliard School (1973-81), and Philadelphia’s University of the Arts (1978-85). Some students were supported by the Canada Council, the America-Israel Foundation, and Bloom’s own waiving of payment, in addition to scholarships provided by the various schools. He held guest professorships and residencies at nearly every major university and conservatory in North America, with appearances at Eastman, Hartt, the University of Michigan, Curtis, the University of Cincinnati, Banff Music Center, the Montreal Conservatory, Carnegie Mellon University, the Milwaukee Chamber Music Institute, and Interlochen, with the Cuyuga Chamber Orchestra of Ithaca, New York, and in San Francisco (Conservatory and Symphony combined), Houston (Symphony and Rice University combined), and Dallas. Summers were spent in residence at the Bennington College Composers’ Conference from 1950 to 1960, the Yale Summer School at Norfolk from 1960 to 1976, the Aspen Music Festival from 1974 to 1976, and the Sarasota Music Festival (formerly New College Music Festival) from its inaugural season in 1964 to his retirement from that festival in 1989.

Beginning with his one year in Rochester, Bloom was continuously active as a private teacher with a studio in his various homes and at Carnegie Hall, and as Professor at Eastman (1936-37), Yale School of Music (1957-76), Hartt (1967-75), the Manhattan School of Music (1967-72), the Juilliard School (1973-81), and Philadelphia’s University of the Arts (1978-85). Some students were supported by the Canada Council, the America-Israel Foundation, and Bloom’s own waiving of payment, in addition to scholarships provided by the various schools. He held guest professorships and residencies at nearly every major university and conservatory in North America, with appearances at Eastman, Hartt, the University of Michigan, Curtis, the University of Cincinnati, Banff Music Center, the Montreal Conservatory, Carnegie Mellon University, the Milwaukee Chamber Music Institute, and Interlochen, with the Cuyuga Chamber Orchestra of Ithaca, New York, and in San Francisco (Conservatory and Symphony combined), Houston (Symphony and Rice University combined), and Dallas. Summers were spent in residence at the Bennington College Composers’ Conference from 1950 to 1960, the Yale Summer School at Norfolk from 1960 to 1976, the Aspen Music Festival from 1974 to 1976, and the Sarasota Music Festival (formerly New College Music Festival) from its inaugural season in 1964 to his retirement from that festival in 1989.

It was during these residencies that Bloom fulfilled his dream to conduct, most memorably shaping heartfelt readings of Mozart’s Serenade in C minor, K. 388 and Dvorak’s Serenade in D minor, Opus 44, B. 77. Bloom first performed K. 388 at Town Hall in NYC in 1948, which was perhaps the premiere performance of this work on the American concert stage. Olin Downes commented in his review for the New York Times, “Think of all the things that happen to the theme of the last movement! The master’s fancy is inexhaustible. And when one recalls the pathetic circumstances of the greater part of Mozart’s existence, during which he produced, with wholly inexplicable fecundity, music of this quality, one remembers the noble Austrian tradition which he observed so bravely and well: the tradition according to which, at a critical moment, the German says that the situation is serious but not hopeless, while the Austrian says that the situation is hopeless, but not serious!”[12] Bloom relished the opportunity to spread this sunny optimism, as he did projecting Bach’s sense of fortitude through his performances with the Bach Aria Group, exuberantly celebrating life’s joys even as the depth of sorrow and despair that befell humanity was also expressed through tender performances. Samuel Baron, a colleague in the Bach Aria Group, wrote of a concert performed in the late 1960s at the Weizman Institute in Rehovoth, “The hush that came over the hall when Bob began to play was awesome. They had plenty of death to think about, that audience–and Bach’s particular mixture of longing for death, and dreading it and fearing it at the same time–it was almost too much for the audience to take. The music was not greeted by applause and smiles. It was received in silent tears and deep contemplation. On the stage we could hardly go on with the concert.”[13]

Bloom’s acceptance of an invitation to teach oboe lessons at an institution such as the Yale School of Music and the Juilliard School was famously contingent on being given the opportunity to coach chamber music for mixed ensemble (winds, strings, keyboard, voice) since he felt that wind players needed the opportunity to study the masterworks that mostly fell into this category (with the notable exception of K. 388 which Mozart originally scored for 8 winds).

Bloom’s acceptance of an invitation to teach oboe lessons at an institution such as the Yale School of Music and the Juilliard School was famously contingent on being given the opportunity to coach chamber music for mixed ensemble (winds, strings, keyboard, voice) since he felt that wind players needed the opportunity to study the masterworks that mostly fell into this category (with the notable exception of K. 388 which Mozart originally scored for 8 winds).

Out of love and respect for his colleagues and former pupils, a radio series currently in preparation, produced in the early 1990s by the Broadcasting Division of the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and entitled The American Oboist, featured Bloom hosting interviews with and performances by leading American oboists. The 23-part series continued with esteemed colleagues stepping in to host subsequent segments after Bloom’s death in 1994.

In addition to Bloom’s concern for the grueling schedules that were becoming de rigor for his younger colleagues as a result of increasingly longer orchestral seasons paired with summer festivals, he also began expressing concern over the back sliding that the American society was falling into vis a vis both private and public support for living wage jobs in the performing arts. In the late 1960s Bloom was even suggesting that a widespread strike by all musicians including matriculating students–perhaps more than one strike– might be needed to have the resulting silence remind Americans of the quintessential role that music plays in our ability to live sensitive, productive, and considered lives; his advocacy for those musicians providing this service to be reasonably compensated was based on his belief in the value to society of its act of sustaining an artist class.

Honors

Bloom was the recipient of many honors, including a Titulo de Reconocimiento from the Organizacion del Festival Casals in 1968; an honorary Master of Music degree from Yale University in 1971; a Certificate of Merit from the Yale School of Music Alumni Association in 1977; an Honorary Life Membership in the Pittsburgh Musical Society in 1978; and an Honorary Membership in the International Double Reed Society in 1985.

In 1968 Yale Reports, a weekly broadcast, taped two sessions of conversations with Bloom and Walfredo Toscanini in celebration of Walfredo’s grandfather’s centennial. Earnest Harrison wrote “A Brief Interlude at Yale with Robert Bloom” for Woodwind World in 1975, the same year that Eugene Cook broadcast “Robert Bloom Talks with Eugene Cook” for WYBC. An article entitled “Robert Bloom, Eminent American Oboist,” by Richard Woodhams, Principal Oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, was published in the December 1989 issue of the Instrumentalist. In 1990, Robert Stumpf II taped an interview with Bloom for Maestrino, the Newsletter for the Leopold Stokowski Society of America. Transcriptions of these and other taped interviews conducted by Julius Baker, Samuel Baron, David McGill, and Susan Eischeid can be found in Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician.[14]

Bloom’s biography is the first entered in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians[15] for an American-born/American-trained oboist.

In the spring of 1988, friends, colleagues, and former pupils gathered in Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York for an 80th Birthday Tribute. Nine segments from this concert are available, released in 2013 on YouTube.[16]

Equally cherished honors were the many photographs inscribed to him by such luminaries as Pablo Casals, who wrote “a Robert Bloom–grand, grand artiste!!!” and Otto Klemperer, who wrote “to my dear Swan of Tuonela.”

Perhaps most dear to Bloom were the frequent comments made that his oboe playing “sang.” Daniel Webster, the long-time music critic of the Philadelphia Inquirer, called Bloom the “epocal oboist” in his obituary. He wrote, “Mr. Bloom is credited with helping to create an American bel canto style of playing that is lyrical, full, and subtly inflected.[17] Eugenia Zukerman led the final dayenu tribute at Bloom’s 80th Birthday celebration with a litany of achievements that ended with “Master of the Bel Canto style.”

Personal Influence

As a member of the first generation of American-born and -trained musicians to play a prominent role in American orchestras and conservatories, Bloom felt fortunate to have encountered many of the crucial figures in the pantheon of 20th-century teachers, conductors, mentors, and colleagues, and to have been a participant in and witness to much of that century’s most important musical developments. Philip Nelson, Dean of the School of Music at Yale University from 1970 through1980, lauded Bloom as a “consummate musician, oboist (and one-time cellist), cabinet maker, exceptional chef, lively pedagogue, raconteur extraordinaire, world traveler, and a ‘gentleman for all seasons,'”[18] one of the most likable champions of the 20th century. Joseph Polisi, President of the Juilliard School, remarked at Bloom’s 80th Birthday Tribute in 1988, ” It’s really been wonderful for all of us to hear all of these speakers talk about how well they have known Robert Bloom, worked with him, admired him, and I certainly fall into that group just as well. But in fact with me, as Bob recently reminded me, he knew me before I was conceived. As a point of explanation, my father, William Polisi, and Bob were colleagues in the NBC Symphony in 1937 and onwards when my father was Principal Bassoonist of that orchestra and Bob was the Principal Oboist. I think the tradition that now goes back over 50 years and the sense of family and the sense of a sharing of the wealth that we all know is a love of music really is centered in Robert Bloom, because we understand that he is a magnificent performer, an extraordinary composer, someone who really knows what the materials of music are all about, but most importantly, he is a very, very special human being. Each one of us in the audience has known him in a slightly different way–for myself, as I said, as my father’s friend, a representative of the finest traditions in music making for this entire century, as a teacher of chamber music when I was at the Yale School of Music with him. But also, I think he represents what music making can and should be and he stands for us all as a representation of what we should strive for. And so, when we think of his vitality, when we think of his warmth, when we think of his concept of phrasing that you will hear in a few minutes in the [Mozart] C Minor Serenade, when we think of his love of music and his family and his friends, I think it’s also a time for us to enrich ourselves and to remember what we can be as human beings and as artists in this society. So, Bob, thank you for being who you are and what you represent, and may you live 80 more years so that we can share in your luster even more.”

To these tributes, as he likely would have to Gunter Schuller’s comment made in 2002, Bloom always responded that it was only through collaboration with great musicians of his time that he was allowed to find and use his unique voice, a voice that might have been stifled in other eras, including today. Schuller wrote, “Bloom was not only a great artist on his instrument but an important scholar and researcher in his field of expertise. He belongs to a period in music when players, especially wind and brass players, were individualist artists who, without distorting the music in some arbitrary, willful way, developed a personal style which was instantly recognizable and memorable. There were others like that in those bygone years, but, alas, instrumental playing has become almost totally homogenized in the last three or four decades. That is why The Robert Bloom Collection is of such historical relevance and an invaluable representation of one aspect of our great American musical heritage.”[19] And indeed why everyone needs to examine the factors of that bygone era and to shoulder responsibility towards living talents, the exceptions to the “almost totally homogenized” landscape who are passionately seeking to maintain a high level of artistry as well as to those who are still in the early stages of their struggle to gain entry to the profession to pursue their personal Endzweck. Should achieving this aspiration be left only to those few who are “lucky,” as Bloom often called himself when reflecting on his own journey?

Summer Breaks and Hobbies

Although even he succumbed late in his career to expectations to perform, coach, and give masterclasses at summer festivals, Bloom maintained that his professional longevity and joie de vivre were the result of his taking time off for at least a month every summer, his secret being to leave himself a “few good reeds” when he stopped playing to use to get back in shape. His summer retreats were Maud Wood’s rooming house in Seal Harbor, Maine during the 1930s and 1940s, his wife’s summer home in Holderness, on Squam Lake in NH, in the 1950s and 1960s, and his summer home on Great Cranberry Island (see website:http://www.cranberryisles.com), Maine from 1970 through the end of his days. Woodworking was his passion beginning in 1940; creating reproductions of early American furniture was one of his greatest joys.

- Backshore, Great Cranberry Island; photo by David Westphal

Pupils

Bloom had one intense style of teaching for all whom he accepted as a pupil. He was not narrowly focused only on placing pupils in major orchestras in America and abroad (Tel Aviv, Johannesburg, Tokyo to name a few locations), although he often did so, but rather on teaching the basic techniques that would give each one as much freedom and as few limitations to their ability to grow under his musical mentorship and beyond throughout their lives. In the spirit of Bloom’s nurturing attitude towards all who cared deeply and worked hard, all of the pupils (that is, all that have been documented to date–corrections are welcome) are listed below with links to their musical affiliations. (For those having multiple affiliations, just one link is provided; the reader can then follow the trail for more information.) Dozens more who attended masterclasses list Bloom as a teacher; others list him as an influence or simply as their inspiration.

- John A. Abberger http://americanbach.org/Artists/AbbergerJohn.htm

- Stephen Adelstein http://www.linkedin.com/pub/stephen-adelstein/60/685/31a

- Robert Atherholt http://music.rice.edu/facultybios/atherholt.shtml

- Frank Avril http://classicalarchives.com/artist/77857.html

- Mark Baker

- Eugene Barnard http://books.google.com/books/about/Survey_of_Oboe_Solos_for_Use_in_Public_S.html?id=916nNwAACAAJ

- David Barnett

- Susan Barrett http://instantencore.com/contributor/bio.aspx?CId=5023630

- John Bennett http://whso.org/about-the-whso/musicians/

- William Bennett III

- Peter Bergstrom http://Raystill.com

- Nancy Berliner http://doctors.dana-farber.org/directory/profile.asp?pict_id=5758020

- Sara Lambert Bloom http://RobertandSaraLambertBloom.com

- David M. Bourns http://cmpr.edu

- Mark Brown http://loc.gov/rr/perform/

- Robert Carpenter http://ridley.ads.delconewsnetwork.com/springfield-pa/communication/newspaper/robert-carpenter/2013-09-04-2222-the-woodwind-express-bob-carpenter

- Deborah Carter

- William Cobb http://lyrichord.com/linernotes/lems8081US.pdf

- Roger Cole http://www.vancouversymphony.ca/artist/roger-cole/

- Randall Cook http://www.scb-basel.ch/index/114135,?_LANGUAGE=en

- Marilyn Coyne http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Marilyn-Coyne/3721846

- Sandra D’Amato http://www.memphissymphony.org/communityengagement

- Judith Dansker-DePaolo http://www.hofstra.edu/Faculty/fac_profiles.cfm?id=323

- Stephen Davis

- Susan Dayton http://www.dachtyl.com/WHSO/Program4.pdf

- Edward Dolbashian http://music.missouri.edu/faculty/dolbashian.html

- William Douglas

- Susan Eischeid http://www.valdosta.edu/colleges/arts/music/bios/susan-eischeid.php

- Marcia Ellis

- Thomas Fay http://www.idrs.org/IDRSBBS/viewtopic.php?id=12654

- Carl Fels http://newscenter.nmsu.edu/articles/view/3178

- David Flacks

- Mark Gainer http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Mark-Gainer/150246302

- G. Rodney Garside http://www.newspapers.com/newspage/31764786/

- Elden Gatwood http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1129&dat=19851114&id=i69RAAAAIBAJ&sjid=2W4DAAAAIBAJ&pg=3062,4323892

- Catherine Gerardi http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/music/faculty/directory#performance-instructors-click-on

- Eileen Gibson http://www.newspapers.com/newspage/61163390/

- Clelia Goldings http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Name/Selim-Aykal/Performer/48697-2

- Robert Goler

- Doris Goltzer http://www.westportnow.com/index.php?/v2_5/comments/heida_hermanns_voice_competition_winners/

- Gay Greschel

- Arnold Gross http://www.linkedin.com/pub/arnold-gross/15/280/847

- Dennis Harper http://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/23/arts/music-debuts-in-review-three-instrumentalists.html

- Earnest Harrison http://www.cmdalsu.com/paa/double-reed-day/

- Jeffrey Harrison

- Peter Hedrick http://cnyarts.org/directory/view/new-york-state-baroque

- Susan Hicks http://www.idrs.org/resources/whoswho/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=12283

- Ruth Holtzman

- Delight Immonen http://www.idrs.org/resources/whoswho/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=12255

- Robert Ingliss http://www.njsymphony.org/musicians-music/musicians/detail/18

- Eugene Isabelle http://www.e-yearbook.com/yearbooks/East_Carolina_University_Tecoan_Yearbook/1969/Page_476.html

- Marsha Jaeger http://cep.berkeley.edu/directory

- Denise Kamradt http://catalog.ucr.edu/1998-99/mus.html

- Thomas Keahey http://books.google.com/books/about/Concerto_in_B_flat_major_André_no_4_for.html?id=qapkmwEACAAJ

- Joyce Kelley http://www.greenwichsymphony.org/history

- Colleen Kennedy http://tbso.ca/about-us/the-orchestra/colleen-kennedy/

- Michael Kenyon http://www.musicusmedia.com/michael.html

- Richard Killmer http://www.esm.rochester.edu/faculty/killmer_richard/

- Katie Koffel

- Fredrick Korman http://www.fredkorman.com/bio.html

- Ezra Kotzin http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/chicagotribune/obituary.aspx?pid=160867880

- Kim Kowalke http://www.esm.rochester.edu/faculty/kowalke_kim/

- Lisa Kozenko http://www.newschool.edu/mannes/faculty-az/?id=4d54-5178-4f44-6379

- Glenn Laguna http://test.woodwind.org/clarinet/BBoard/profile.html?f=10&id=9268

- Barbara Landeen

- Phyllis Lanini http://www.nytimes.com/1988/12/15/arts/reviews-music-mixed-program-by-boehm-quintette.html

- Jerry Lazar http://www.jerrylazar.info/writing.html

- Diane Lesser http://www.newyorkpops.org/musicians

- David Lichtenstein https://soundcloud.com/relativity-error/rhapsody-in-blue

- Marc Lifschey https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marc_Lifschey

- Michael Lipton

- Susan Logan http://www.rocky.edu/academics/academic-programs/undergraduate-majors/music/Faculty.php

- Richard Lottridge http://www.reallygoodmusic.com/rgm.jsp?page=composers2&compid=123655

- Humbert Lucarelli http://humbertlucarelli.com/

- William Lynch

- John Mahan http://www.memorialfuneralhome.com/obituaries/John-Mahan/#!/Obituary

- Robert Martenson http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2229&dat=19590329&id=BHYmAAAAIBAJ&sjid=OwAGAAAAIBAJ&pg=2876,3771934

- Paul McCandless http://www.paulmccandless.com/

- Roger McDonald http://ir.lib.umt.edu:8080/xmlui/handle/10844/1078

- Tamar Melzer http://www.ipo.co.il/eng/About/Members/___%20_____%20___/____/Musicians,227.aspx

- Shelly Mesirow http://www.worldcat.org/title/bay-area-womens-philharmonic-82681/oclc/336127323

- Kurt Michaelis http://digitalassets.ushmm.org/photoarchives/detail.aspx?id=1171032

- Patricia Morehead http://www.patriciamorehead.com/

- Ryohei Nakagawa https://www.pipers.co.jp/e/nakagawa/

- Bruce Neuman

- Patricia Grignet Nott http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/1997-05-21/lifestyle/9705200207_1_new-world-symphony-cleveland-orchestra-music-director

- Stephen Parkany http://dmsymphony.org/site/uploads/NotesSept.pdf

- William Parrish http://www.emu.edu/bach/artists/bill-parrish/

- Gerald Pav http://partypop.com:8888/vendors/search?page=2&sort=Vendor.priority&direction=asc&keywords=Oboe+Players&location=San+Pedro%2C+CA&category=3176

- Peggy Pearson http://winsormusic.org/artisticdirector/

- Ilona Pederson http://www.linkedin.com/in/ilonnapederson

- Vanessa Pentz-Adamo http://madisonacademyofmusic.com/new-haven-ct-meet-our-staff.htm

- Janet Piez http://worldcat.org/digitalarchive/content/server15982.contentdm.oclc.org/BSYMO/PROG/TRUSVolume8/Pub411_1974-1975_Trip_BushMem_1974-10-07.pdf

- Oded (Udi) Pintus http://www.icor.freeservers.com/archive.html ;

- Carolyn Pollack http://www.nyphilomusica.org/concerts/08-09/artists.html

- Seth Powsner

- Ronald Quinn http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Ron-Quinn/1522449614

- Andrea Ridilla http://miamioh.edu/cca/academics/departments/music/about/faculty-staff/woodwinds/andrea-ridilla.html

- Kay Roylance

- Bernard Rubenstein http://www.bakkentoday.com/event/article/id/357835/publisher_ID/1/

- Carol Rupert http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2512&dat=19710310&id=sBNIAAAAIBAJ&sjid=dQANAAAAIBAJ&pg=3391,1153568

- Rogene Russell http://www.fineartschamberplayers.org/about-us/history/

- James Ryon http://music.unt.edu/faculty-and-staff/detail/288

- Mark Salkind http://www.urbanlegendnews.org/features/2011/11/09/getting-the-scoop-on-urbans-head-of-school-mark-salkind/

- Lucinda Santiago http://laguardiahs.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Open-House-Booklet-14.15-Finala.pdf

- Harry Sargous http://www.idrs.org/resources/whoswho/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=12039

- Gary Schultheis http://www.oneworldsymphony.org/artists_symphony.shtml

- Margaret Schultz

- Earl Schuster http://boards.ancestry.com/surnames.schuster/228/mb.ashx?pnt=1

- Francine Schutzman http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Francine-Schutzman/303846997

- Phyllis Secrist http://www.music.utk.edu/faculty/secrist.html

- William Joseph Seidel http://www.reinhardt.edu/academics/music/music_faculty.html

- Mina Seidman-Haas http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/albumList.jsp?name_id1=62704&name_role1=4&bcorder=4

- Rheta Naylor Smith http://www.idrs.org/publications/controlled/DR/DR13.2/DR13.2.Belfy.ObRec.html

- Jennifer Sperry http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Jennifer-Sperry/61109196

- David Spitzer

- Robert Sprenkle http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/SPRINKLE/2003-07/1059066037

- Barbara Todd Sprenkle http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/SPRINKLE/2003-07/1059066037

- Patricia Stenberg http://www.wusf.usf.edu/patricia_stenberg_honored_in_memorial_concert

- Ray Still http://www.raystill.com

- Daniel Stolper

- Caesar Storlazzi http://news.yale.edu/2009/09/04/director-aid-his-office-offers-more-financial

- John Symer http://www.nytimes.com/1995/07/09/arts/classical-music-at-peace-in-the-lonely-realm-of-the-oboe.html

- Bobby Taylor http://nashvillearts.com/2010/06/08/bobby-taylor-sculpting-his-voice-on-the-oboe/

- Stephen Taylor http://music.yale.edu/faculty/taylor-stephen/

- Robert Thompson http://panufnik.com/works/soloists-orchestra/

- Joel Timm http://music.usc.edu/joel-timm/

- Larry Timm http://www.fullerton.edu/arts/music/faculty_Pages/timm.html

- William Ulrich, Jr http://7aso.org/htmldocs/reunorch06.htm

- Eugene Vance http://seattletimes.com/html/obituaries/2015138514_vanceobit22m.html

- Alice VanLeuvan (Hekster)

- John Viton http://www.moreheadstate.edu/content_template.aspx?id=859&folderid=476

- Allan Vogel

- Jerry Voorhees http://www.southeastern.edu/acad_research/depts/mus/faculty/bio/voorhees.html

- Susan Vought http://music.gmu.edu/perfarts/archives/spring07/3.31.07%20Oboe%20Day.pdf

- Louise Brown Waite

- David Weiss http://www.latimes.com/local/…/la-me-david-weiss-20140530-story.html

- Tamar Beach Wells http://www.gbs.org/language/english/tamar-beach-wells-principal-oboe

- Abby Rosenberg Wells http://www.newspapers.com/newspage/60637172/

- Elizabeth Wheeler http://www.arkansassymphony.org/themusic/orchestra/

- JoAnn Baxter Wich http://www.hopkins.edu/ftpimages/82/misc/misc_78716.pdf

- Coco Widmar http://tcnj.pages.tcnj.edu

- Paul Winter http://www.paulwinter.com/

- Paul Wolfe http://www.mysuncoast.com/news/local/paul-wolfe-the-driving-force-behind-the-sarasota-music-festival/article_58f8fc4e-f344-11e3-aabb-001a4bcf6878.html

- Doreen H. Wunsch http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Doreen-Wunsch/488564027

- Phillip Young http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/phillip-t-young-emc/

- Avinoam Yosselevitch http://english.isb7.co.il/

- Mary Beth Zimmerman

References

- Jump up^ Hoberman, Jerome, “A Biographical Sketch,” Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician (Limited Edition, 2009), p. 3.

- Jump up^ Storch, Laila, Marcel Tabuteau: How Do you Expect to Play the Oboe If You Can’t Peel a Mushroom? (Indiana University Press, 2008), p. 188.

- Jump up^ Bloom, Robert, Letter in Bloom archive, Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, p. 104.

- Jump up^ Webster, Daniel, “Profile of Robert Bloom on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday,” Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, p. 6.

- Jump up^ Stokowski, Leopold, Letter in Bloom archive, Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, p. 106.

- Jump up^ LaBelle, June, “Interview with members of the Bach Aria Group on the occasion of their final concert,” IBM’s Salute to the Arts (WQXR, New York, 1980).

- Jump up^ Lundstrom, Harold, Review of the Bach Aria Group concert in Salt Lake City, November 1960, Deseret News.

- Jump up^ Bloom, Sara Lambert, Liner Notes for “The Art of Robert Bloom: Chamber Music” Vol I, Boston Records BR1033CD

- Jump up^ Eddy, Timothy, Letter (1999) in Bloom archive.

- Jump up^ Jacobson, Bernard, Review of “The Art of Robert Bloom: Music for Oboe and Strings,” Vol. I, Boston Records, BR1031CD, Fanfare, May 2000.

- Jump up^ Emerson, Gordon, “Famed Oboist Retiring: Au Revoir, Not Goodbye,” New Haven Register, 1980.

- Jump up^ Downes, Olin, Review of New Friends of Music concert at Town Hall, New York, New York Times, 1948

- Jump up^ Baron, Samuel, Letter in the Bloom archive, Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, p. 252.

- Jump up^ Various authors, Interviews transcribed, Robert Bloom: The Story of a Working Musician, pp. 3-55.

- Jump up^ The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Oxford University Press, 2nd Edition, 2001)

- Jump up^ Nine YouTube links from A Tribute to Robert Bloom on his 80th Birthday at Alice Tully Hall (1988)

- Jump up^ Webster, Daniel, Obituary: “Robert Bloom; Premier Oboist Played With Phila. Orchestra,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 18, 1994.

- Jump up^ Nelson, Philip, Retired Dean, Yale School of Music, Citation at Bloom’s retirement event (May 1976) in Bloom archive.

- Jump up^ Schuller, Gunther, Citation (2002) in Bloom archive

External Links

- Official website

- Discography on official website

- Obituaries: February 16, 1994 New York Times

- February 18, 1994 Philadelphia Inquirer

- Dissertation: The American School of Oboe Playing: Robert Bloom, John de Lancie, John Mack, and the Influence of Marcel Tabuteau by Galbraith, Amy M., D.M.A., WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY, 2011, 101 pages; 3476409

- Dissertation: The Legacy of Oboist and Master Teacher, Robert Bloom by Janna Leigh Ryon, D.M.A., UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, 2014

Profile of Robert Bloom

On the occasion of his 80th birthday

by Daniel Webster

The Marcel Tabuteau Room at the Curtis Institute of Music is full of dark oak paneling and dark resonances for those who want to sense them. Tabuteau’s memory has become legend, and his influence on oboe playing in America has blossomed into legend, too. It was in this room last winter that Robert Bloom met students during a week in which he coached and prepared students for a concert in Curtis Hall.

Bloom was not intimidated by the setting or by the photographs on the walls showing Tabuteau, usually in overcoat and smiling haughtily down into the camera. He was at his working pace from the moment he entered, and he passed over greetings quickly to get to the work at hand, the Brahms Clarinet Trio. He students were individuals, not yet a trio and a little skeptical of what they might learn in an hour or so with an oboist. They started, played for a while, and stopped while Bloom suggested that the cellist turn her chair slightly toward what would be the front of the stage. That bit of indirection led to his showing the cellist how to present the first notes, heard alone. Present them, not play them, and in an almost diffident suggestion about bowing, Bloom led the cellist into discovering in that opening musical statement tonal and expressive implications that her partners called inspiring.

The trio members were playing from different editions, it turned out, but Bloom brushed that aside. He stressed phrasing truths and Brahmsian gestures that could be achieved by specific means in each instrument. The mood had subtly changed from the distant one of students and teacher to a unity in which four musicians were discovering truths that none had quite known. By the end of the session, the students were almost a trio, and Bloom saw them out with a smile that reflected his admiration for them.

Sitting in that room afterward, Bloom looked back over the sixty years that separated his student days from this coaching session. He had worked with Tabuteau in this room–and others–and his memory was not clouded by sentiment.

“Tabuteau was a distinct personality and so inspired us to think of ourselves as individuals rather than a mere color in the orchestra. But as the demands on orchestral instrumentalists grew, we had to add new dimensions to our playing. Perhaps because singing played such a large part in my early years, I wanted my playing to sing.”

In that appraisal, Bloom was unconsciously describing the quality that has made his playing the touchstone for two generations of musicians. One of his colleagues, clarinetist Vincent Abato, recently retired from the Metropolitan Opera, said, “He is the Stradivarius of the oboe,” he said, “the king of them all, because of that musical mind. He never played a note in his life; it was always music.”

Bloom had apparently brought that quality to Curtis in one of the showiest arrivals at a school accustomed to prodigies and breathtaking talents. He had had to buy an oboe to audition since his acquaintance with oboe was almost casual. Bloom laughed at that. “I had grown up in Pittsburgh, and I used to go to the Grand Theater in my neighborhood. The orchestra there was pretty good, and the conductor got to know me and he liked me. I had heard a lot of music at home. My father, Julius, was a cantor, and I sang in his choir. I had a brother who was already in New York playing violin, and I imagined that I would be a musician.

“I composed, I played piano and violin, and then, probably because of what I heard at the Grand, I decided I would play the saxophone. My parents called my brother in New York–he was their advisor in musical matters, and he talked me into studying the cello instead. I studied cello at Carnegie Tech for a couple of years, but I still had my eye on the Grand Theater. I tried other instruments and began playing the oboe a little. The teachers I knew encouraged me, and finally somebody suggested I apply at Curtis.

“I hardly knew how to play the instrument, and when Curtis wrote back to set an audition, my brother in New York stepped in again, and we found a used oboe I could play in the audition.

“That audition was strange. Tabuteau asked me to play scales, and he said , ‘It won’t take you long.’ I was accepted.”

Tabuteau’s judgment was right. It took three years.

When Carlos Salzedo heard that Bloom had been offered a position in the Cleveland Orchestra, he took it upon himself to speak to Stokowski about the young oboist. Stokowski’s reply was something that Bloom to this day chuckles over: “Tell that young man that it is much closer from Curtis to the Academy of Music than it is to Cleveland.”

“I had signed my contract before Stokowski asked to hear me play,” Bloom said. “He wanted me to play English horn, and I said I’d try it. He told me he wanted me to stop playing the oboe altogether so that I would think like an English hornist. That was okay.”

The three-year wonder became one of the orchestra’s advertisements. Julius Baker, the flutist, recalled “When I went to Curtis a few years after Bob, the students all had favorites in the orchestra, but everybody said, ‘Wait until you hear that English horn player.’ They were right.”

Bloom said he would have been happy to stay on, but “I began to get a little tired of Franck, Dvorak, and Tchaikovsky. Jose Iturbi was conducting in Philadelphia and he asked me if I had ever thought about being a first oboist. ‘Every day,’ I told him, and he hired me to play in the Rochester Philharmonic in 1936.”

“I had hardly started in Rochester when we all heard that Toscanini was forming the NBC Symphony.” Bloom was contacted and offered the position as solo oboe. “I felt great loyalty to Iturbi for giving me the chance to play first oboe and also felt that I was not good enough yet to play for Toscanini. When I expressed my hesitation to Iturbi, he said, ‘Don’t be a damned fool. You have a chance to play with Mr. Music, don’t refuse.’

Unselfconscious talents can afford to be modest, but Bloom had vaulted over an established field of players, as he had at Curtis, to take the premiere orchestral position in America. In six seasons, he was heard by national audiences in broadcasts. Unfortunately, his tenure with Toscanini did not come when the orchestra was recording as busily as it was to do later. Many Toscanini recordings feature an Italian oboist who, most say now, only Toscanini could admire.

His restless nature led him to step from the NBC Symphony to the free-lance world. There he was solo oboist in the Columbia Symphony, the RCA Red Seal Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski’s orchestra, the Bell Telephone Hour, orchestras recording with Igor Stravinsky, and with virtually every other recording orchestra. Two generations of record buyers grew up knowing Bloom’s oboe playing without knowing who it was.

And when William Scheide founded the Bach Aria Group in 1946, Bloom was the obvious choice to play the cantatas and chamber music. Far ahead of his time, he had studied deeply in Baroque performance practice to set the work of the Bach Aria Group apart from the norm of Bach performance in mid-20th-century America. That association, and the New York concerts, the world tours, and recordings finally presented Bloom as a soloist equal in stature with Eileen Farrell, Bernard Greenhouse, and Julius Baker. The association lasted until 1980, when Bloom was looking toward a semiretirement.

Bloom was a teacher almost as long as he has been a player. Few major American orchestras are without Bloom students in principal roles. He had his own studio in Carnegie Hall, and was on the faculty at the Manhattan School, Yale from 1959 to 1976, Juilliard, Hartt College, and the Philadelphia College of the Performing Arts. Richard Woodhams, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s solo oboist, then a teenager, had first met Bloom at a summer program in Reno, Nevada, an association Woodhams calls pivotal in his own life as an oboist.

Bloom’s wife, Sally Lambert, herself a pupil from Yale, appraised his teaching philosophy. “He taught us highly developed techniques so that we could develop musically. He was tireless in his efforts to develop chamber music in the curriculum. To us, he exemplified the great marriage of talent and discipline in his playing and teaching, and he made it possible for us to become individuals by demanding the same approach from us.”

Of Bloom’s playing, Woodhams said, “He was the first American to combine a deep quality with a real singing style. It is part of him; he’s a humanistic guy. I like his enthusiasm and the warmth he still has for the profession. He has certainly left an imprint on all of us. Musically, I’d say he combined the objective ideas of Tabuteau with natural musicality and intuition.

“I used to like watching him play. He rarely moved, you know, and he practiced to make it look easy. And he always had a very live, warm tone. His playing was refined, but never bland, combining energy and control. In his teaching he always emphasized instrumental technique to serve the music. He told us to have a conception and then develop the technique to fulfill it. And he always played and taught with tremendous energy,” Woodhams said.

His colleagues second that. Abato said, “Sometimes when we were starting a rehearsal, Bob would play an A, and I would think that I would never hear anything more beautiful than that note all day.

“I think I was the one who first called him ‘Coach.’ That was his nickname while we were playing in New York. He told us all how to play–and nobody objected.”

Baker said, “Bob’s forte is sound, but he’s a teacher all the time. He likes to tell us all how to play, but he set such a high standard we couldn’t object.”

Woodhams has a list of favorite recordings with the anonymous Bloom playing the oboe solos. “If you have heard Milhaud’s “La Creation du Monde” with Baker, Benny Goodman, you have heard a great performance. But I treasure the “Afternoon of a Faun” he made with Stokowski and Baker, Sibelius’ “Swan of Tuonela” in which he plays English horn, and that terrifically anachronistic “Water Music” he made with Stokowski.”

Woodhams said nothing had told him as much about Bloom as a dinner they had together a couple of years ago at Woodhams’s house.

“We had a couple of drinks before, and had wine with dinner, and all at once Bob said he wanted to see my studio. I did and he saw an oboe lying there, and he said, ‘I want to play.’ He hadn’t played the oboe for a few years, but he picked it up and picked up a reed that was just lying there. He didn’t even soak it; he just put it in the oboe and played. There was all the sound, the music, and the passion that I remembered. That was his way: he had always heard the oboe and then made it happen.”

This piece was commissioned for the commemorative program booklet for Robert Bloom’s 80th Birthday Tribute at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center in New York in 1988 and was reprinted in the Philadelphia Inquirer, for which Webster has served as a distinguished music critic for many decades.

Famed oboist retiring

Au revoir, not goodbye

by Gordon Emerson

New Haven Register

March 16, 1980

Robert Bloom, world-acclaimed oboist and Yale professor emeritus, has decided that this is the last year he will play in public. . . .

In case you’re thinking that Bloom is leaving formal concert life due to failing powers, the oboist quickly dispels such a notion. During a conversation early last week, Bloom was extremely candid about the decision. “Sure, I have a few mixed emotions about it,” he admitted, “but I’m tired of practicing and I just don’t want the pressure of concerts any more. I don’t care how long you’ve been playing, when you step on a stage, it’s not like going to a picnic. Actually, I think I’m playing as well as I did 10 years ago, and this past year has been one of my best. But I don’t have anything more to prove and I’ve played it all.”

. . . . Giving up public performances does not in any manner mean retirement, however. Bob Bloom has always been an extremely energetic man, and since recuperating from a heart attack seven years ago his immense vitality remains undiminished. Rather, playing only for his own enjoyment [ed: which he never did] will allow more time for endeavors that have necessarily been subordinated by his busy performing career. Bloom has composed several works for oboe, and he noted, “For a long time I’ve wanted to write an oboe concerto and now I’m going to do it. [ed: But he never did.] Also, over the years I’ve edited a great deal of baroque music and Sara and I plan to assemble it all and have it published. So I’m really looking forward to next year.

Robert Bloom: A Biographical Sketch

by Jerome Hoberman with Robert Bloom

Cincinnati 1990

R

obert Bloom was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1908. His father was Julius Bloom, Pittsburgh’s leading cantor, who besides officiating in the city’s synagogues was an outstanding choir director. The family was musical, Bloom’s sister an excellent soprano and pianist, his brother a violinist who later became a member of the New York Philharmonic. Robert Bloom sang in his father’s choir, and studied several instruments while attending local public schools. He entered Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology as a student of cello and music education in 1925. Encouraged by the conductor of Pittsburgh’s All-City Youth Orchestra to take up the oboe, Bloom auditioned in 1927 and won a place in the oboe class at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, which had opened just three years before. At Curtis, his teacher was Marcel Tabuteau, long-time Principal Oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who is generally thought of as creator of the American school of oboe playing. Tabuteau was less interested in the past experience of potential students than in their aptitude for the oboe, and was quite willing to take on someone who was virtually a novice.

Bloom joined the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski in 1930, first as Assistant Principal Oboist, later as Solo English Horn; in May 1935, he was awarded his diploma from Curtis. Leaving the Philadelphia after six seasons, he became Principal Oboist of the Rochester Philharmonic. In 1937, with the formation of the NBC Symphony Orchestra, Bloom was offered the position of Principal Oboe by Artur Rodzinski, who was organizing the orchestra for Arturo Toscanini and who, as conductor of the Curtis Orchestra while Bloom was a student, knew his playing well. Despite misgivings due to his limited experience as a first-chair player, Bloom accepted the post, encouraged in this decision by Jose Iturbi, conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic. He remained with Toscanini and the NBC Symphony until 1943.

Two years after leaving NBC, Bloom was one of the cofounders of the Bach Aria Group, which became a seminal influence on the postwar Baroque revival. During this period of his career, he was also active in recording studios as Principal Oboist for Columbia, Decca, and RCA Victor records under conductors such as Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Otto Klemperer, Leopold Stokowski, Igor Stravinsky, Artur Rodzinski, William Steinberg, Leonard Bernstein, Erich Leinsdorf, and Jose Iturbi, among others. Many of these classic recordings remain available in the current catalogues. Bloom also distinguished himself as a soloist and chamber musician, with appearances throughout the United States and in South America, Europe, and Israel. He retired from the Bach Aria Group in 1980.

Beginning with his one year in Rochester, Robert Bloom has been continuously active as a private teacher and as Professor at Eastman (1936-37), Yale School of Music (1957-76), Hartt (1967-75), the Manhattan School of Music (1967-72), the Juilliard School (1973-81), and Philadelphia’s University of the Arts (1978-85). He has held guest professorships and residencies at nearly every major university and conservatory in North America, with recent appearances at Eastman, Hartt, the University of Michigan, Curtis, the University of Cincinnati, Banff Music Center, the Montreal Conservatory, Carnegie Mellon University, the Milwaukee Chamber Music Institute, and Interlochen, with the Cuyuga Chamber Orchestra of Ithaca, New York, and in San Francisco (Conservatory and Symphony combined), Houston (Symphony and Rice University combined), and Dallas. Summers have been spent in residence at the Bennington College Composers’ Conference from 1950 to 1960, the Yale Summer School at Norfolk from 1960 to 1976, the Aspen Music Festival from 1974 to 1976, and the Sarasota Music Festival (formerly New College Music Festival) from its inaugural season in 1964 to the present. Former pupils hold or have held principal positions in the Chicago, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Houston, Portland, Oregon, New Jersey, Toronto, and Vancouver Symphonies, the Los Angeles and Rochester Philharmonics, and the Los Angeles and Saint Paul Chamber Orchestras. Bloom’s teaching is carried on by former pupils who hold professorships at the Eastman and Hartt Schools of Music, the California Institute of the Arts, Indiana and Rice Universities, and the Universities of Cincinnati, Michigan, and Southern California.

Robert Bloom has been the recipient of many honors, including an honorary Master of Music degree from Yale University in 1971. In the spring of 1988, friends, colleagues, and former pupils gathered in Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York for an 80th Birthday Tribute. An article entitled “Robert Bloom, Eminent American Oboist,” by Richard Woodhams, Principal Oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, was published in the December 1989 issue of the Instrumentalist.

Although his performing career has ended, Bloom remains active as a composer, with works for oboe with strings and oboe with piano performed frequently throughout the world. In addition, Bloom’s ornaments, elaborations, and cadenzas for much of the standard oboe repertoire of the Baroque and classical periods are regularly in use, with and without authorization. A radio series currently in preparation, produced by the Broadcasting Division of the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and entitled The American Oboist, will feature Bloom hosting interviews and performances by leading American oboists.

As a member of the first generation of American-born and -trained musicians to play a prominent role in American orchestras and conservatories, Bloom feels fortunate to have encountered many of the crucial figures in the recent history of musical performance as teachers, mentors, and colleagues, and to have been a participant in and witness to much of this century’s most important musical developments.